In the first of a planned ongoing series of lengthier “biography” posts to highlight specific ancestors of mine, this post will feature my 6x-great-grandfather John Coward. I descend from John through his daughter Barbara, then through her daughter Agnes Atkinson, her daughter Eliza Smith, her daughter Agnes Eliza Phoebe Collingwood, her son Harry Collingwood Mitton, and finally through his son John Lawrence Mitton, who was my grandfather.

John Coward

(c1726-1816)

“…A man of wayward and singular disposition…”

One ancestor of mine – my 6th great-grandfather to be exact – is a curious one. Whilst there are very few historical records that relate to him, due to his descendants – most notably his grandson – attending Oxford and Cambridge universities (yet having come from meagre ‘peasant’ backgrounds), there are a number of publications written between 1825 and 1983 that mention him, and give a more human description of his character than any baptism record or marriage bond could ever do.

The most recent of the aforementioned publications was an article published in 1983 in the “Transactions of the Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society”, written by Kenneth Harper, M.A., M.LITT., who had also published an earlier article in 1950 about some of my Collingwood ancestors (who were also the descendants of John Coward). Harper’s article references an much earlier written piece from 1825 that was a first-hand account written by John Coward’s grandson Solomon Atkinson, titled “Struggles of a Poor Student through Cambridge”. It is this account that provides much of the information about John Coward, from the mouth of someone who actually knew him personally.

John Coward’s exact date of birth is not known; no baptism records for him can be found in either Cumberland nor Westmorland (the two likeliest counties of his birth). He was either born elsewhere or the records have been lost to time. It is estimated that he was born around 1726 because his grandson Solomon recounts visiting John in the winter of 1816, when John was “on the verge of ninety winters.”

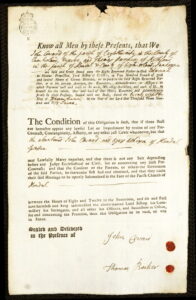

The earliest document that can accurately place John is his marriage bond, dated 28th December 1757. He is described as being “of the parish of Crosthwaite, in the County of Cumberland, weaver”. Crosthwaite is a small village in the Lake District, about halfway between Kendal and Lake Windermere. A marriage bond was essentially a document in which the couple alleged that there were no impediments to the marriage. The groom and his bondsman (usually a close friend or relative) were set a financial penalty that would be payable if the allegation should be proven false (such as either already being married, or the couple were related). In the case of John Coward and Thomas Barker (his bondsman), this amount was set at £200 (around £20,000 in 2021). The amounts were deliberately set high to deter irregular or illegal marriages.

John’s wife-to-be was Agnes Atkinson, a spinster, of Kendal. A marriage bond does not prove that the couple did actually marry, only that they had the intent to. Considering they went on to have a child, it can be assumed that they did indeed marry in Kendal soon after.

One of John and Agnes’ children was my 5x great-grandmother Barbara Coward. Barbara’s own marriage bond document in 1794 states that she was at 21, but it is worth noting that recording someone’s age as 21 on marriage bonds usually meant they were at least 21, i.e. of age to marry, but could have been older.

Assuming she was born immediately after her parents’ marriage, the earliest possible year of birth for Barbara would be 1757, and the latest year would therefore be 1773, assuming she was actually 21 when she married. Solomon Atkinson’s account mentions that “whilst still young [his father John Atkinson], married a woman of some property, Barbara Coward, who was nine years older than John.” Luckily an actual baptism record for John Atkinson can be found in Lazonby, Cumberland on the 22nd March 1773, meaning if Solomon’s information is accurate, Barbara was born around 1764.

There is a noticeable gap between John Coward and Agnes Atkinson’s marriage in 1757 and Barbara’s supposed birth in 1764, so it would be safe to assume that they had other children before Barbara. Searching baptism records for any Coward born to parents John Coward and Agnes does turn up two more candidates – Betty Coward baptised in Kendal in 1758 and Mary Coward born on the 7th September 1760 in Windermere.

The next time John Coward is mentioned in records after his daughters’ baptisms is Barbara’s marriage bond in 1794. The bond is raised by Barbara’s husband-to-be John Atkinson and her father John Coward, who is described as being “of Ambleside in the County of Westmorland, weaver.” The bond also shows that Barbara also lived in Ambleside at the time of her marriage.

The last time John Coward is found in any documentation is in a UK Land Tax Redemption document in 1798, where he is shown to be living in Kirkby Kendal.

All of the other information that is known about John comes from the aforementioned account by his grandson Solomon. Some time around 1816, Solomon (aged around 18 at the time) was struggling to raise any money to pay for his education. Having had no help from the rest of his family, he decided to visit his maternal grandfather (John Coward) to ask for assistance. He describes the journey to John’s house as “a long day’s journey of sixty miles on foot, in the depth of winter” and his small property as “one of those wild and beautiful dells which insinuate themselves among the masses of mountain on the borders of Yorkshire and Westmoreland” – presumably somewhere near Kendal – that John obtained through “the accumulation of great industry and economy through a long life”.

John is described by Solomon as “a man of a wayward and singular disposition” and one who “had for many years estranged himself from every branch of his family”, yet his “ruling passion was still strong, and he deprived himself of every thing which could alleviate the infirmities of age.”

John in fact did help out Solomon and his kindness can be seen in how Solomon describes the encounter:

I stated to him my views, hopes, and prospects, with all the natural eloquence of youth and enthusiasm . The old man was pleased; I can even now see the stern and rugged features of his fine countenance relaxing into a feeling of sympathy and kindness. He had not for many years heard the voice of affection – it therefore touched his heart the more readily. His ordinary feelings and acquired habits gave way; he opened his heart and his purse – he tendered me £100 and gave me his blessing.

How shall I describe the unutterable emotions that swept through my heart; words never did, words never can, express the frantic joy that thrilled through every fibre of my frame. He did not live to see the measure of my success – to see the realisation of that which then concentrated in one absorbing object all my energies, feelings, and desires. Perhaps he could not have appreciated the nature of that success, even had he lived; but he would have rejoiced when he saw me rejoice; he would have been happy when he saw the smile of triumph sparkle on my brow. Neither has he seen the sufferings and privation which awaited me after; and it is some consolation to think that if he did not joy in my success, neither were his last moments saddened by my hopeless fortunes.

Harper’s article suggests that John died aged 90 in 1816, although I have not been able to find any burial record to confirm this.